| about | works | articles | catalogues | links | contact | home |

| HAROLD J. TREHERNE

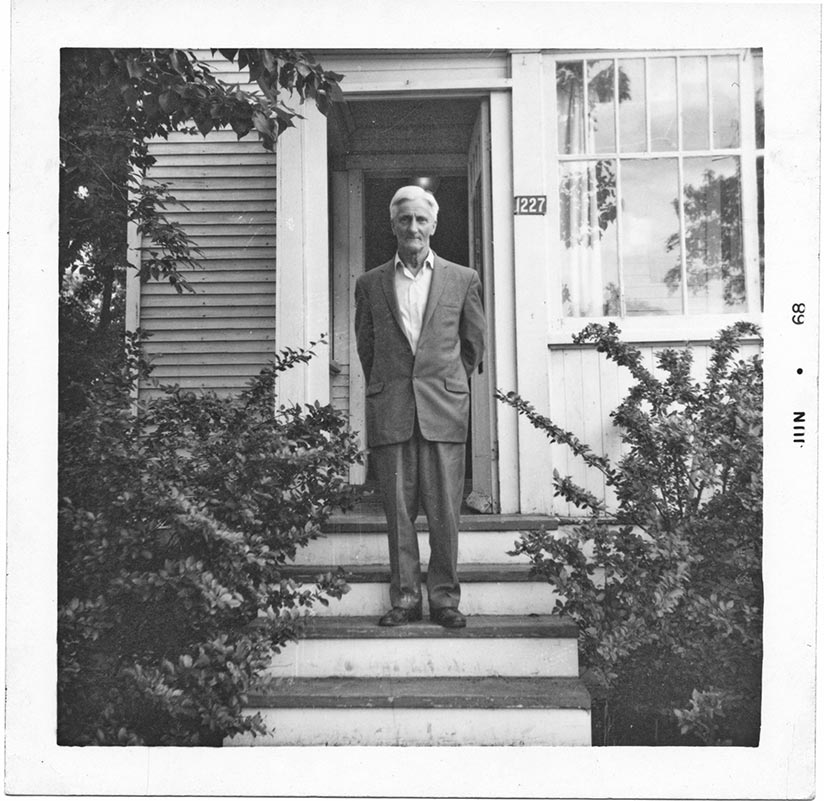

Harold J. Treherne (1899-1975) was one of several Saskatchewan grassroots artists whose intention was to represent daily life as accurately as possible. Like his contemporaries, Wesley Dennis (1899-1981) with whom he was acquainted and Robert Vincent (b. 1908), the simple everyday complexities of landscape and townscape were a primary concern for Treherne. Unlike Dennis and Vincent, he also applied this criterion of accuracy to residential interiors, humorous or narrative still lifes, and drawings of intricately decorated plates. Dennis and Vincent occasionally did works based on their memories of earlier years, but Treherne had to work with his subject before him or from photographs. He dealt with his past by writing about it rather than by drawing it. Treherne was one of many greenhorn hired hands whose ineptitude has become part of prairie folklore. But he recognized his inexperience and worked hard to prove himself. By good fortune he first worked in the Mawer district near Central Butte north of Moose Jaw which had been settled by the English. Treherne felt accepted there and enjoyed the western informality, the open spaces and the challenges of hard work. He returned to Yorkshire in the winters, but by 1926 he was ready to settle permanently in the Mawer district. With the help of his father (who checked the prospects with the local banker first), Treherne acquired a half-section of land, machinery, seven horses, feed, a cow, two pigs and a grubstake. Shortly afterward he married Dorothy Williams, a close friend from England. They were to spend nearly twenty years on the farm at Mawer, during which time they had three children. In 1945 they moved to Moose Jaw when an additional half section was acquired. As far as can be determined, Treherne did not do any drawing during this period, but sometime during the 1940's he began to write of his experiences in prose and poetry. Many farmers kept notebooks about prices and weather and incidents in their lives. Treherne expanded this to include poems and those personal reflections which he might have shared with others had he been a less solitary individual. He would later admit to his friend and Moose Jaw neighbour Bert Kitts that he had not been a good farmer. Although he enjoyed farming he had failed to learn how to work marginal land as productively as others could and nature often seemed to win the game she played with him. Nevertheless, after his earnest efforts had been destroyed by storms, frost and drought he remained optimistic. As he described it, a sight, sound or smell could restore his faith: "Down but not out, so does the leaven of sunlight dissipate the gloom and rekindle the spirit."3 The picture that emerges of Treherne from family and friends is of a trusting man, inquisitive, frugal, inventive and shy, who nonetheless (like so many grassroots artists) thought well of himself. He did not socialize much but he did have friends with whom he liked to joke. However, he could be easily hurt if he were on the receiving end of a barb. The traditional prairie pastimes of hunting, curling and cards did not interest him, and he tended to prefer more solitary pursuits (such as taking apart his several clocks and putting them back together). His son John recalls how quickly Treherne could do arithmetic in his head. Friends remember his quiet determination; difficulties would simply firm his resolve. Treherne was one example of a not uncommon type of western farmer. Tinkerers and inventors for fun and necessity,4 part-time philosophers musing on the meaning of things and the coincidences of life, folk painters or writers and poets who were reserved yet uninhibited by tradition. They were sturdy individualists - often eccentric, frequently cantankerous and almost invariably stubborn. Their inventiveness, self-reliance and determination could make anything possible. Treherne had never lost his early interest in drawing. In 1957, as his children began to leave home, he began, like the farm tinkerer, with the materials around him. His first subjects were from his surroundings, usually calendars and magazine pictures. But he liked complexity and had the confidence to approach more difficult and demanding subjects. Turning to the interiors of his Moose Jaw home and working fairly large, he executed two views of the kitchen, one from each end (Hall and Kitchen). With strong perspective he put to paper everything in sight. Every floor tile, stair step, shelf, knick-knack and doorway from foreground to background in equal detail. Nothing must be left out . . . after all, it was there. And as would become his habit in his interior work, he included a small reference to himself: his drawing hand reflected in the toaster on the kitchen table.

HALL AND KITCHEN, February 1957 (detail) Severely diagonal, full of detail, these two early works serve to introduce Treherne's subject matter and to demonstrate a difficulty he would not admit but later would accommodate and use. Although he had been an apprentice draftsman in his youth and claimed to "sight" or measure with a ruler, his perspective was often multiple. With equal attention to detail throughout a picture, the whole effect would occasionally get lost in the attempt to control everything in sight. It appears that when he turned his head to see all before him, he would create another and then another vanishing point, thus a panoramic view would result. It was "true" but the viewer had to accept several vanishing points to accommodate the work. This unique complexity became one of the most intriguing elements of Treherne's work. Treherne drew his pictures, then applied the colour. He liked the contrast ball-point pen afforded and numerous night scenes are among his best work. Treherne would do the drawing during the day, when he could see and include all the detail, then he would apply the colour at night (often working from a window or vestibule) to make certain it was correct. This frequent use of windows gave him a convenient way of framing the outdoors, of defining the space so that it conformed with his careful controlled methods. Often the window frame itself is included, as in Winter Work (1965). Working outdoors without such a frame he tended to draw everything, often resulting in works encompassing as much as 180 degrees. Treherne was a man of order and regularity. Since the move to Moose Jaw his pattern was to drive to the farm Monday morning and spend the week there, returning to town on Saturday morning. A movie would complete his Saturday, on Sunday he would attend St. Andrew's United Church, and Monday morning would see him back to the farm. He continued to farm a quarter section after his wife's death in 1967 until the mid-seventies. The loss of his wife left Treherne with bouts of depression that could last for weeks. His wife had acted as an intermediary with the rest of the world - initiating contacts with friends and neighbours, smoothing over situations where Treherne's brusqueness might be misunderstood. Easily angered by what he thought were assaults on his integrity, Treherne could be uncomfortable in social situations. His shyness and his wife's past intercessions left him inexperienced at social interaction after she was no longer there to help him out. In seeking to adjust to his loss Treherne found a new home in regular visits to the Moose Jaw Art Museum. Director Austin Ellis and Joan Goodnough provided a friendly atmosphere and easy afternoons of banter and talk. The caretaker, Jim Kelly, was a fellow Yorkshireman, and they joked and kidded one another in a warm friendship. Treherne became a fixture, an unofficial resident artist. Setting up his board and equipment in the foyer or by a window he would draw St. Andrew's Church (Night) [1968], Art Museum (Interior) [1968], and Winter Scene (St. Andrew's Social Hall) [1969]. "Look there, it's all framed,"5 he would say, pointing to the view through the window. As he grew to feel at home at the art museum, Treherne regained his high spirits. His arrival would be signalled by a little "shuffle dance" step on the hall tile from the library and he would often challenge Austin and Joan to read without aid some small, delicate printing he had done. Legend has it that one day he even did a somersault in the office. He did not view himself as old and refused to visit any senior citizens drop in centres. Treherne also relied increasingly on his friendship with the Kitts family in Moose Jaw and friends in the Central Butte area. Neighbours since the early 1950's, the Kitts offered Treherne a friendly oasis where he could sit and talk, play pool, or even fall asleep on the couch. Treherne always acknowledged his friendship with (and gave works of art to) these friends and neighbours. He also travelled to each of his sons' and daughter's homes, redecorating with his pictures and working from their windows. Glaslyn (Night) [1966], at once typical and specific, was done from the second floor of the RCMP barracks where his daughter Pat and her husband lived. These trips to family and friends have given us some of his best work as he recorded rural Saskatchewan winter and summer, day and night. This insistent bracketing he would do throughout his life. The inquisitive desire to acknowledge it all is present from his earliest work in which he draws the kitchen from one end and then the other, right through to the day and night versions of St. Andrew's Church, the back yard at 1227 5th Ave. N.W., and Glaslyn, Saskatchewan. They tell us that the ordinary and the everyday is something to examine and study. Treherne could make the ordinary complex and the complex appear simple. His works repay the viewer for time invested in looking and comparing. Treherne satisfied his need for recognition by entering numerous amateur art competitions. Until recently the Watrous Art Salon held in Watrous, Saskatchewan was the largest amateur art competition in Western Canada. It was a week-long exhibition that included comments by the juror before the assembled artists. Treherne had often entered and won. At one Salon in the early 1970's a juror had awarded all the prizes for "modern" art. Treherne disliked this kind of art, but when the juror made critical and unsympathetic comments in public about his work he was angered and then depressed. Always quick to take offence, unable to accept criticism even as a joke, Treherne was devastated by this public criticism. He felt that all of his efforts were for nought, that this single criticism denied and denigrated his entire life. Treherne's response was to turn to his other form of self expression for validation. He decided to prove the worth of his life by publishing stories about it which he was sure people would want to read. But the farm magazines to which he sent material did not agree. In one of those same magazines he found an ad for a vanity press that promised to sell and promote an author's work. Gathering together stories, poems, and illustrations, Treherne sent his work off to New York with high hopes. But it was a vanity press, the projected costs increased again and again and the publication date dragged over two and one-half years. Treherne wrote letters, became depressed, and even visited New York in efforts to get his project completed. The stress affected his health and his art. He ceased drawing during this period. On December 7, 1973 he entered Moose Jaw Union Hospital for three periods ending in mid February 1974. He liked the attention and friendliness of the hospital and in gratitude gave the hospital a version of Track and Field (1970). When the book finally came out he was relieved, confident that he had proved something. He began to draw again, and the Glenbow Museum in Calgary mounted an exhibition of his work. He submitted again to the Watrous Art Salon, and shortly after the Glenbow exhibition closed he travelled to England to visit family. Treherne died July 14, 1975, at his nephew's in England, not knowing that once again he had won at the Watrous Art Salon. Harold Treherne's insistent recording of his environment has created for us a body of important grassroots art. His inquisitive nature and his mathematical bent sought expression in a myriad of playful visual tricks which intrigue the eye and force us to look again. Highly individual and yet accessible, his work makes us quietly conscious of our aloneness in even a populated landscape. He reminds us to be still for a while and look at our relationship to ourselves and our surroundings. Despite our efforts to control, populate and exploit our landscape, a work such as SPC and the Farm (1961) makes it clear that we are always at the mercy of Mother Nature. Treherne's night views are unique in Saskatchewan folk art. Attracted no doubt to the precise quiet clarity of western winter nights, he produced drawings of residential exteriors which strike a deep emotion in the prairie resident. Glaslyn Night (1966) must certainly be the definitive small town portrait in all of Saskatchewan art . . . scattered small homes, community hall, refuse burning in an oil drum, lonely street lights that seem to emphasize the sparseness of the town and the new Canadian flag hanging quietly in front of the RCMP detachment. In Treherne's book Murder, Inc. - In a Keg, the last poem is written to his departed wife Dorothy. The last three lines reflect the artist's underlying feelings of mankind's need for permanence:

Against this magnitude of impersonal forces, Treherne attempted to discover order through his art. W.P. Morgan from "HAROLD J. TREHERNE: A Retrospective" an exhibition organized and circulated by the Dunlop Art Gallery, Regina, 1983-1985. ISBN 0-9690121-9-5

|

| about | works | articles | catalogues | links | contact | home |